Vienna: Otto Wagner’s architectural legacy

Above/featured: On the Linke Wienzeile, opposite the Naschmarkt at right. Photo, 18 May 2018 (6D1).

What: Among many are 2 key structures: Post Savings Bank, Steinhof church.

Why: Some of the most important architectural examples of 20th-century modernism.

Where: Many examples found throughout the city of Vienna.

“Wagner School” included Josef Hoffmann, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Jože Plečnik.

To visit Vienna is to know Otto Wagner. A first-time visitor to the city will be forgiven for not knowing about Wagner or his creations, but throughout their time spent in the Austrian capital, they’ll encounter Wagner’s early 20th-century “Modern Architecture”.

Vienna is for many the city of Beethoven, Mozart, and Strauss; the city of historic and stylish cafés with coffee and Sacher Torte; the city whose pride is revealed in the combined World Heritage Site that are the classic period architecture within the Old Town and the beautiful palace and gardens at Schönbrunn. Flowing through the city is the Danube river, memorialized in Johann Strauss II’s “An der schönen blauen Donau” (The Blue Danube).

The evolution of architectural style is plainly evident throughout the city. Around the Ringstrasse (inner ring road) is architecture in the Historicism style, with big nods to Neoclassicism in the Parliament, Neo-Gothic in City Hall and the Votivkirche, and a lot of Neo-Renaissance represented by the City Theatre, Art History Museum, Natural History Museum, Opera House, and the University.

But as calendars flipped from 1899 to 1900, the fin-du-siècle heralded a move to bold thinking, different style, and a change in the way and reasons why buildings were put together. Consequently, Vienna is a city of 20th-century modernism whose traces are found in art, architecture, and urban planning. Even with post-war reconstruction in the mid-20th century and a mindful push for environmental rigour in the 21st-century, Vienna still remains in many ways Otto Wagner’s city.

Modern Architecture began with (Charles Rennie) Mackintosh in Scotland, Otto Wagner in Vienna, and Louis Sullivan in Chicago.– Rudolph Schindler, who studied architecture under Otto Wagner (Sarnitz 2005).

Wagner Modernism

Wagner’s architectural designs were informed by contemporary “best of classic” architectural styles exhibited on the city’s Ringstrasse, but Secession, Art Nouveau, and “modernism” took hold, shaping Wagner’s nascent ideas and designs to meet and match the demands of function with appropriate form. With the latest advances in materials technology, he created a new visual language connecting and combining the visual aesthetic of urban architecture with the required functional elements served by the buildings. There are over two dozen examples on display in the city, including apartment buildings and buildings for public and private enterprise. He was also tasked by the city to design and construct the city’s new Stadtbahn or municipal railway, including all necessary technical and mechanical fixtures required to operate a transport system. Many of his station buildings (e.g., U4, U6) remain in use today.

The Wien Museum provided the following description:

As “architect of the metropolis,” Otto Wagner was an important European architect working at the turn of the 20th century. He was one of the first to demand a new style of architecture which was based entirely on function, material, and construction, and which would meet the needs and challenges of “modern life.” Wagner’s radical attitude and belief in progress clashed with a prevailing fear of modernization, which sparked heated debates and would be a big reason why many of his visionary designs remained only on paper. Today, Wagner’s buildings are considered milestones on the road to “functional modernism.” His book “Moderne Architektur” was a founding manifesto to 20th-century architecture.

At the front of one of his villas in the city’s western suburbs are the following quotes:

– Sine arte sine amore non est vita. (There’s no life without love or art.)

– Artis sola domina necessitas. (Necessity is art’s only mistress.)

Otto Wagner died in 1918 and is buried in Vienna’s Hietzing cemetery.

1857–1859: student at the k.k. Polytechnische Institut, in Vienna.

1859–1860: architecture student at the Königliche Bauakademie, in Berlin

1861–1862: architecture student with August Sicard von Sicardsburg and Eduard van der Nüll at the Akademie der bildenden Künste, in Vienna.

1894–1912: professor of architecture at the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna.

Wagner Places & Traces

I highlight the following examples of Wagner’s creations in Vienna and in the nearby city of Baden about 25 km to the southwest. Every numbered item corresponds to the numbered location in the map below. Wagner’s design and development of Vienna’s municipal railway will be described in a separate post.

- Akademie der bildenden Künste

- Ankerhaus, 1894

- Bellariastrasse Miethaus, 1869

- Denkmal für Otto Wagner, 1930 by Josef Hoffmann

- Döblergasse Miethaus, 1911

- Friedhof Hietzing, 1918 (family grave)

- Grabenhof, 1875

- Kirche am Steinhof, 1907

- Köstlergasse Miethaus, 1898

- Lobkowitzplatz Miethaus, 1884

- Lupuspavillon, 1908

- Majolikahaus, 1898

- Musenhaus, 1898

- Neustiftgasse Miethaus, 1909

- Nussdorfer Wehr, 1898

- Österreichische Länderbank, 1884

- Österreichische Postsparkasse, 1903–1912

- Palais Hoyos, 1891

- Rennweg Miethaus, 1891

- St.-Johannes-Nepomuk-Kapelle, 1895

- Schützenhaus, 1908

- Stadiongasse Miethaus, 1883

- Universitätsstrasse Miethaus, 1887

- Villa Wagner I, 1886

- Villa Wagner II, 1912

- Wien Museum Karlsplatz

- Wien Museum Pavillon Karlsplatz, 1898

- Baden bei Wien: Villa Hahn, 1885

- Baden bei Wien: Villa Epstein (Rainer), 1867

• Sources

Akademie der bildenden Künste

Academy of Fine Arts.

Address: Schillerplatz 3, 1st district (Innere Stadt).

Architecture student: 1861–1862.

Architecture professor: 1894–1912.

Academy of Fine Arts in morning light from Schillerplatz. Photo, 15 May 2022 (X70).

Ankerhaus, 1894

Anker commercial building.

Address: Graben 10, 1st district (Innere Stadt).

Public transport: U-Bahn U1 or U3, to station “Stephansplatz”.

Wagner designed the Anker-Versicherung insurance office and commercial building (Büro- und Geschäftshaus der Anker-Versicherung) with modern versatility and functionality. His design created a new kind of classification for multipurpose buildings that included offices, stores, apartments, and a studio. As commercial space, the two floors closest to ground level were completely encased with glass; this kind of “transparent curtain” was very unusual at the time. The building rooftop included a functioning glass-and-iron construction photography studio, which differed with surrounding buildings whose cupolas or roof structures were simply decorative. The facade here at “Zum Anker” would foreshadow his landmark Majolikahaus and Musenhaus buildings four years later; see these 2 latter buildings below. Today, Helvetia is a descendant of Anker-Versicherung, and operates its insurance company offices within the building.

On the Graben, facing southwest to Ankerhaus; note how the bottom two floors are encased in glass. Photo, 20 May 2018 (X70).

Left: Building at Graben 8 (1887). Right, Ankerhaus at Graben 10, with enclosed glass structure on the roof. Photo, 1 Jul 2025 (P15).

Bellariastrasse Miethaus, 1869

Bellariastrasse apartment block.

Address: Bellariastraße 4, 1st district (Innere Stadt).

Public transport: U-Bahn U3 to station “Volkstheater”; Tram to stop “Ring/Volkstheater”.

Bellariastrasse apartment block (by Otto Wagner); Palais Epstein (by Theophil Hansen & Otto Wagner). Photo, 15 May 2022 (X70).

Bellariastrasse apartment block; the facade is not original. Photo, 15 May 2022.

Denkmal für Otto Wagner, 1930

Otto Wagner memorial, by Josef Hoffmann.

Address: Makartgasse 2, 1st district (Innere Stadt).

Public transport: U-Bahn U1, U2, or U4, to station “Karlsplatz.”

The four panels for Hoffmann’s memorial to Otto Wagner are:

“Dem grossen Baukünstler Otto Wagner” / To the great architect Otto Wagner

“Geboren Penzing 1841, Gestorben Wien 1918” / Born in Penzing 1841, died in Vienna 1918

“Der Österreichische Werkbund im Jahre 1930” / Austrian Craftwork Association, 1930

“Erneuert von der Gemeinde Wien im Jahre 1959” / Restored by the municipality of Vienna, 1959

Josef Hoffmann’s 1930 memorial to Otto Wagner, at the northwest corner of Makartgasse and Getreidemarkt, next to the Akademie der bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts). Photo, 15 May 2022.

Döblergasse Miethaus, 1911

Döblergasse apartment block.

Address: Döblergasse 4, 7th district (Neubau).

Public transport: Bus 13A or 48A, to stop “Kellermanngasse”; Bus 13A or Tram 46 to stop “Strozzigasse”.

Blue tiles. Photo, 6 Jun 2023.

Aluminum studs at the front door. Photo, 6 Jun 2023.

“The great architect Otto Wagner lived, worked, and died in this building, 1912–1918. Austrian Architectural Society.” Photo, 6 Jun 2023.

Friedhof Hietzing, 1918

Hietzing cemetery, Wagner family mausoleum.

Address: Maxingstraße 15, 13th district (Hietzing).

Public transport: U-Bahn U4 to station “Hietzing”.

Otto Wagner is buried in Hietzing cemetery in the family mausoleum he designed himself in 1881 shortly after his mother’s death in 1880 (one, two). I described some notable people buried at Hietzing cemetery.

Otto Wagner and family: 13-Gft-131. Photo, 16 May 2018.

Grabenhof, 1875

Grabenhof commericial building.

Address: Graben 14–15, 1st district (Innere Stadt).

Public transport: U-Bahn U1 or U3, to station “Stephansplatz”.

Front facade; check out the “gilded balcony” and red painted columns. Photo, 18 May 2023.

Kirche am Steinhof, 1907

Steinhof church; also known as St. Leopold Church.

Address: Baumgartner Höhe 1, 14th district (Penzing).

Public transport: Bus 47A to stop “Baumgartner Höhe”, or bus 48A to stop “Klinik Penzing”.

Up on the city’s Baumgartner Heights is Europe’s first modernist church Kirche am Steinhof or Steinhof Church. Known also as the Church of St. Leopold, the structure is one of the city’s finest examples of turn-of-the-century architecture. Designed and built by Otto Wagner, the church was inaugurated in 1907 for patients of the Steinhof Psychiatric Hospital, which is now a part of the Klinik Penzing complex. The roof is topped with a copper-covered dome whose golden appearance in daylight merits the moniker “Limoniberg” (lemon hill) that’s visible for miles around.

The church was a collaborative effort with other Viennese artists, including mosaics and stained glass by Koloman Moser, angel sculptures by Othmar Schimkowitz, and exterior tower sculptures by Richard Luksch. The Steinhof church and the Austria Post Savings Bank building (see below) are period masterpieces of architecture and two of Wagner’s most important creations.

• Click • for more images and separate description here.

Front facade – 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Sculpted by Richard Luksch, the two tower figures represent Lower Austria’s patron saints St. Leopold and St. Severin at left and right, respectively – 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Front detail with sculptural angels by Othmar Schimkowitz and stained glass by Koloman Moser. Photo on 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Köstlergasse Miethaus, 1898

Köstlergasse apartment block.

Address: Köstlergasse 3, 6th district (Mariahilf).

Public transport: U-Bahn U4 to station “Kettenbrückengasse”.

As his own contractor and client, Wagner built a triplet of apartment houses opposite the Naschmarkt in Vienna: Linke Wienzeile 38 and 40 (see below), and Köstlergasse 3. These three buildings were known as the Wienzeilenhäuser or the Wienzeile Buildings. Köstlergasse 3 was constructed in the Art Nouveau style, and Wagner lived for a time in the ground-floor apartment, famous for the legendary glass bathtub. Wagner built for modernity, showed his creations for modernity, and lived with his creations as a sign of changing modernity (from the 19th- into the 20th-century).

Köstlergasse 3, one of Wagner’s residence buildings – 16 May 2018 (6D1).

Lobkowitzplatz Miethaus, 1884

Lobkowitzplatz apartment block.

Address: Lobkowitzplatz 1, 1st district (Innere Stadt).

Public transport: U-Bahn U1 or U3, to station “Stephansplatz”.

Augustinerstrasse, facing northwest; the Lobkowitzplatz Apartments is the yellow building with the corner cupola. Photo, 19 May 2022.

Entrance to Lobkowitzplatz Apartments, with the “Otto Wagner” stylized green metal work. Photo, 19 May 2022.

Lupuspavillon, 1908

Lupus pavilion

Address: Steinlegasse 28, 16th district (Ottakring).

Public transport: bus 46A or 46B, to stop “Steinlegasse”.

Today, the building is part of the Ottakring clinic: “Klinik Ottakring: Pavillon 24 – 5. Med. mit Endokrinologie, Rheumatologie und Akutgeriatrie mit Ambulanz.

View of the building from Steinlegasse; facility is a working hospital and not open for general access. Photo, 28 May 2023.

Majolikahaus, 1898

Majolica building.

Address: Linke Wienzeile 40, 6th district (Mariahilf).

Public transport: U-Bahn U4 to station “Kettenbrückengasse”.

Opposite the busy Naschmarkt market space at address Linke Wienzeile 38 and 40 are the buildings Musenhaus and Majolikahaus, respectively. The Majolika House is named because the exterior wall is covered in square panels consisting of glazed earthenware or ceramic Majolica tiles. On these tiles, Wagner’s student Alois Ludwig designed the decorative elements with brightly coloured flowers and plants. The green refers directly to the colour scheme used in the city’s municipal railway, also designed by Wagner.

Majolikahaus and Musenhaus, at left and right, respectively – 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Majolikahaus: The garland of flowers seem to spill over the roofline.

Roof cornice and frontage tiles. Photo on 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Apartment balcony, its decorative railing, and detail in the tiles – 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Musenhaus, 1898

Muses building ; also, Medaillonshaus / Medallions building.

Address: Linke Wienzeile 38, 6th district (Mariahilf).

Public transport: U-Bahn U4 to stop “Kettenbrückengasse”.

Next to the Majolikahaus is the Musenhaus or the Muses’ House. The building is named for the exterior plaster facade on which styled gold medallions of muses appear. The medallions also give this building the name Medaillonshaus or Medallion House. The gilded relief medallions, palm fronds, and golden tendrils were designed by Koloman Moser. Anchoring the roof line are Othmar Schimkowitz‘s sculptures of female figures shouting out into the space.

Both Majolikahaus and Musenhaus have uniform verticality and uniform storey heights, with apartments designed with equal functionality and value. Wagner’s trio of Wienzeilenhäuser (Wienzeile Buildings) provided exceptional cases for urban architecture in the city’s burgeoning Art Nouveau movement. All three buildings and their newly furnished apartments displayed Wagner’s growing vision for sophisticated living and new ideas about modernism leading into the 20th-century.

Musenhaus and Majolikahaus, at centre and left, respectively – 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Musenhaus: The palm fronds seem to hang over the roof with corner sculptures by Othmar Schimkowitz.

Musenhaus detail by Koloman Moser. Photo on 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Each “medallion” includes a muse – 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Neustiftgasse Miethaus, 1909

Neustiftgasse apartment block.

Address: Neustiftgasse 40/Döblergasse 2, 7th district (Neubau).

Public transport: Bus 13A or 48A, to stop “Kellermanngasse”; Bus 13A or Tram 46, to stop “Strozzigasse”.

“Neustiftgasse 40.” Photo, 6 Jun 2023 (X70).

“Neustiftgasse 40.” Photo, 6 Jun 2023 (X70).

Nussdorfer Wehr, 1898

Nussdorf dam/weir.

Address: Schemerlbrücke, 20th district (Brigittenau).

Public transport: U-Bahn U4 to station “Heiligenstadt”, then tram D to stop “Nussdorf S”. Alternatively, S-Bahn train S40 to station “Nussdorf”.

Vienna established itself on the banks of the Danube river, but experienced major periods of flooding in low-lying areas over the centuries. Civic projects attempted to tame the Danube at large by the 2nd-half of the 19th-century by regulating the river’s flow and prevent flooding. Between 1870 and 1875, the Danube was straightened to allow safe improved navigation for shipping, and included an artificial channel called the Donaukanal (Danube Canal). Additional river management projects included construction of low dams (weirs) and overflow or control gates (sluices). At Nussdorf from 1894 to 1898, Otto Wagner designed and put up a weir and sluice to control the water flow into the Danube Canal. Opened in 1898, the Schemerlbrücke bridge hovers over the weir with proud bronze lions facing north on one side of the bridge and beautiful light fixtures on the other side.

Schemerlbrücke bridge; the 2 bronze lions are by sculptor Rudolf Weyr. The inauguration year of 1898 is shown at left as Roman numeral “MDCCCIIC” because horizontal space on the bridge pier was restricted; the common Roman numeral representation for 1898 is “MDCCCXCVIII”. Photo on 19 May 2018 (X70).

Sluice-control and administration building – 19 May 2018 (X70).

Facing north from the bridge along the canal, towards the Danube river, flowing left to right. Photo on 19 May 2018 (X70).

On one of the bridge pylons is “Viribus unitis” (“With united forces”), which was the personal motto of Emperor Franz Joseph I, and symbolized the might of the Austria-Hungarian empire. Photo on 19 May 2018 (X70).

Österreichische Länderbank, 1884

Austria National Bank, former headquarters.

Address: Hohenstaufengasse 3, 1st district (Innere Stadt).

Public transport: U-Bahn U2, to station “Schottentor”.

Former Austrian National Bank (Österreichische Länderbank); present-day home to Austria’s federal ministry of “art, culture, public service, and sport” (Bundesministerium der Kunst, Kultur, öffentlicher Dienst, und Sport). Photo, 30 May 2022 (X70).

“No. 3 Hohenstaufengasse”, “ANNO 1884”. Photo, 30 May 2022 (X70).

Österreichische Postsparkasse, 1906

Austria Post Savings Bank, former headquarters.

Address: Georg-Coch-Platz 2, 1st district (Innere Stadt).

Public transport: U-Bahn U3 to station “Stubentor”; U-Bahn U1 or U4, to station “Schwedenplatz”.

Built by Otto Wagner between 1904-1912, the Austria Post Savings Bank with its detached glass-and-steel construction is deliberately set back from the Ring road to emphasize the building’s different appearance compared to the surrounding “historical constructions.” As masterpieces, this bank building and the Steinhof church (see above) are considered two of the most important pieces of architecture by Wagner. The building facade is encased in a layer of thin white marble panels fastened by aluminum-headed steel bolts, giving the appearance of a “secure money box”. This look was always the intent, constructed within the style afforded by purpose and function. The bank was completed in two construction phases from 1903 to 1912. This building was home to the headquarters BAWAG PSK, the fourth largest bank in Austria. In early-2019, the BAWAG Group moved out and into a new building near the city’s central station. With construction plans for condominiums, the building remains open to visitors who wish to view the foyer, atrium, and modest architectural museum inside.

The Post Savings Bank building and the Steinhof church (see above) are period masterpieces of architecture, and two of Wagner’s most important creations.

1:50 scale model of the savings bank by Roland Stadlbauer, 2017. Central “avant-corps” (front facade); note on the roof an angel sculpture which would be realized by Othmar Schimkowitz. Vienna Modernism centenary exhibition at Wien Museum Karlsplatz; photo, 20 May 2018 (X70).

Austria Post Savings Bank, front exterior. Photo, 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Rooftop angel, by Othmar Schimkowitz. Photo, 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Building interior, main hall, facing west; glass construction for both roof and floor maximized natural light streaming into the floors here and below. Photo, 18 May 2018 (6D1).

Palais Hoyos, 1891

Hoyos Palace; present-day Embassy of the Republic of Croatia.

Address: Rennweg 3, 3rd district (Landstrasse).

Public transport: Tram 71 to stop “Am Heumarkt”; U-Bahn U1, U2, or U4, to station “Karlsplatz.”

Palais Hoyos (Rennweg 3). Photo, 24 May 2022 (X70).

Rennweg 3 (Palais Hoyos), Rennweg 5. Photo, 24 May 2022 (X70).

Northwest view on Rennweg; labelled are buildings number 3 (Palais Hoyos) and number 5; Belvedere and the Gardekirche church are at left and right, respectively; a small grove of trees at lower-left is at Schwarzenbergplatz (Schw.). Photo, 13 May 2023 (X70).

Rennweg Miethaus, 1891

Rennweg apartment block.

Address: two entrances at Rennweg 5 and Auenbruggergasse 2, 3rd district (Landstrasse).

Public transport: Tram 71 to stop “Am Heumarkt”; U-Bahn U1 (U2,) or U4, to Karlsplatz.

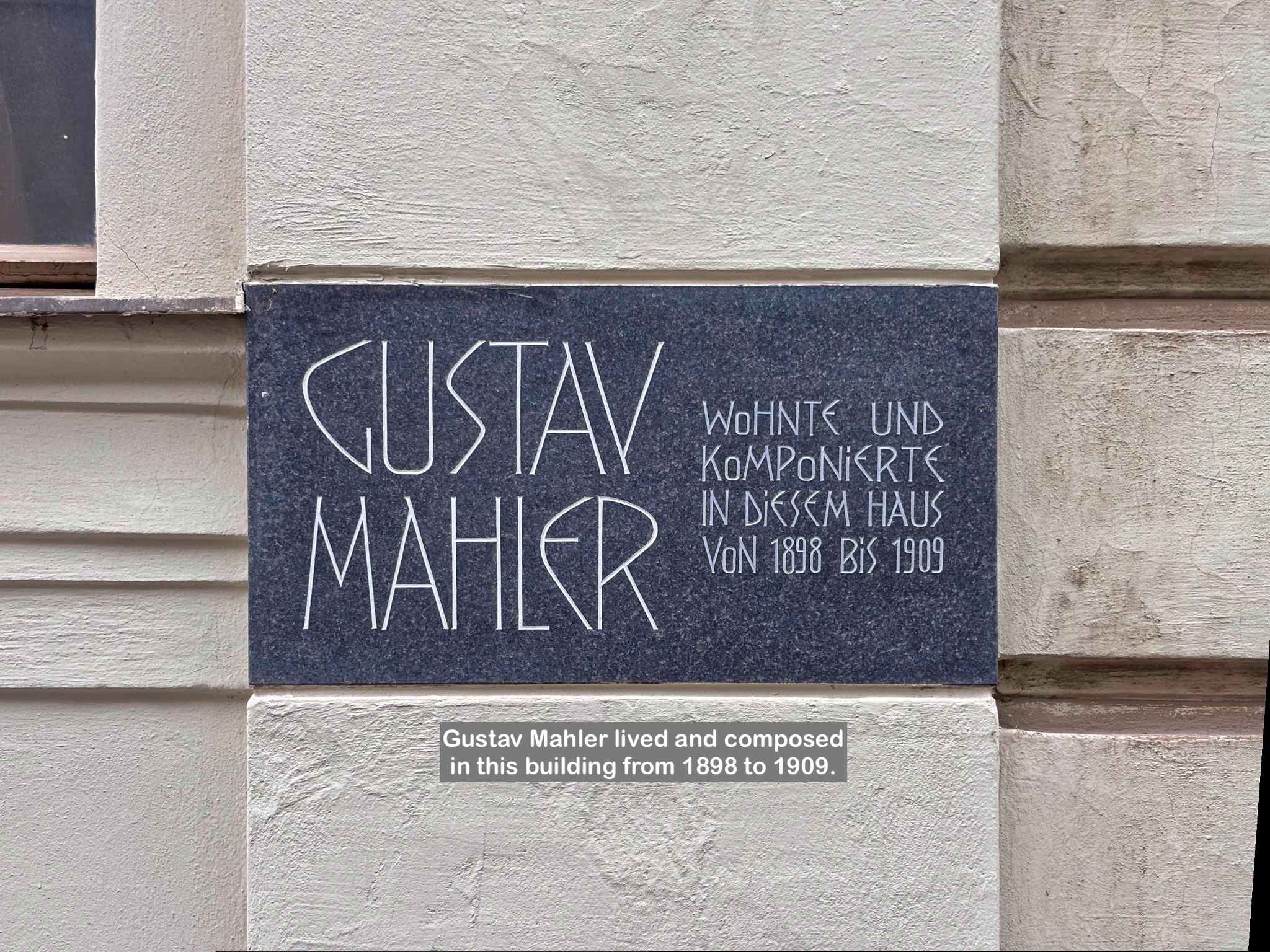

Composer Gustav Mahler called address “Auenbruggergasse 2” (this very same building) his home between 1898 and 1909; the Mahler family rented the building’s entire upper floor as their residence.

Wagner’s building at Rennweg 5 has an additional entrance at address Auenbruggergasse 2, visible at lower right. Photo, 27 Jul 2025 (P15).

Next to the entrance at Auenbruggergasse 2 is a memorial plaque for Gustav Mahler. Photo, 27 Jul 2025 (P15).

St.-Johannes-Nepomuk-Kapelle, 1895

St. John of Nepomuk chapel.

Address: Währinger Gürtel bei U-Bahn-Bogen 115, 9th district (Alsergrund).

Public transport: U-Bahn U6 to station “Währinger Strasse/Volksoper”.

The construction of this modest chapel provided the blueprint a decade later for his grand Steinhof Church project; see above. The cupola or dome for both churches look very similar.

St.-Johannes-Nepomuk-Kapelle, next to the elevated U6 tracks and railway arch at Währinger Gürtel – 8 Jun 2022.

St. John of Nepomuk Chapel, from Klammergasse – 8 Jun 2022.

Schützenhaus, 1908

Former flood-control building; now restaurant.

Address: Obere Donaustrasse 26, 2nd district (Leopoldstadt).

Public transport: U-Bahn U2 or U4, to station “Schottenring”.

Schützenhaus, across the Danube canal from Schottenring station – 25 May 2022 (X70).

Schützenhaus, from the Schwimmende Gärten and across the Danube canal. Photo, 27 May 2023 (X70).

Stadiongasse Miethaus, 1880

Stadiongasse apartment block; now, Embassy of Colombia.

Address: Stadiongasse 6, 1st district (Innere Stadt).

Public transport: Tram on the Ringstrasse (ring road), to stop “Rathaus” or “Parlament”.

Present-day Embassy of Colombia, formerly apartment block – 25 May 2022.

Universitätsstrasse Miethaus, 1887

Universitätsstrasse apartment block, also called “Hosenträgerhaus”.

Address: Universitätsstrasse 12, 9th district (Alsergrund).

Public transport: Tram 43 or 44, to stop “Landesgerichtsstrasse”.

Hosenträgerhaus: Universitätsstrasse 12. Photo, 27 Jul 2025 (P15).

Villa Wagner I, 1886

Address Hüttelbergstrasse 26, in the 14th district (Penzing).

Public transport: Bus 43B, 52A, or 52B, to stop “Campingplatz Wien West 1”.

Former Villa Otto Wagner I; now, Ernst Fuchs Museum. Photo, 3 Jun 2022 (X70).

“Brunnenhaus”, by Ernst Fuchs (1991), next to the Ernst Fuchs Museum. Photo, 3 Jun 2022 (X70).

Villa Wagner II, 1912

Addresses Hüttelbergstrasse 28, in the 14th district (Penzing).

Public transport: Bus 43B, 52A, or 52B, to stop “Campingplatz Wien West 1”.

Former Villa Otto Wagner II. Photo, 3 Jun 2022 (X70).

Front entrance, to former Villa Otto Wagner II. Photo, 3 Jun 2022 (X70).

Wien Museum Karlsplatz

Address: Karlsplatz 8, in the 4th district (Wieden).

Public transport: U-Bahn U1, U2, or U4, to station “Karlsplatz.”

In celebration of the century of Vienna Modernism in 2018, a detailed exhibition of his architectural designs was on display at the Wien Museum Karlsplatz. After renovations (2019–2024), the museum reopened in late-2024, and the permanent exhibition includes a number of Otto Wagner pieces.

Vienna Modernism centenary exhibition at Wien Museum Karlsplatz; photo on 20 May 2018 (X70).

Uncompleted sketch portrait of Otto Wagner by artist Egon Schiele in 1910. Vienna Modernism centenary exhibition at Wien Museum Karlsplatz; photo, 20 May 2018 (X70).

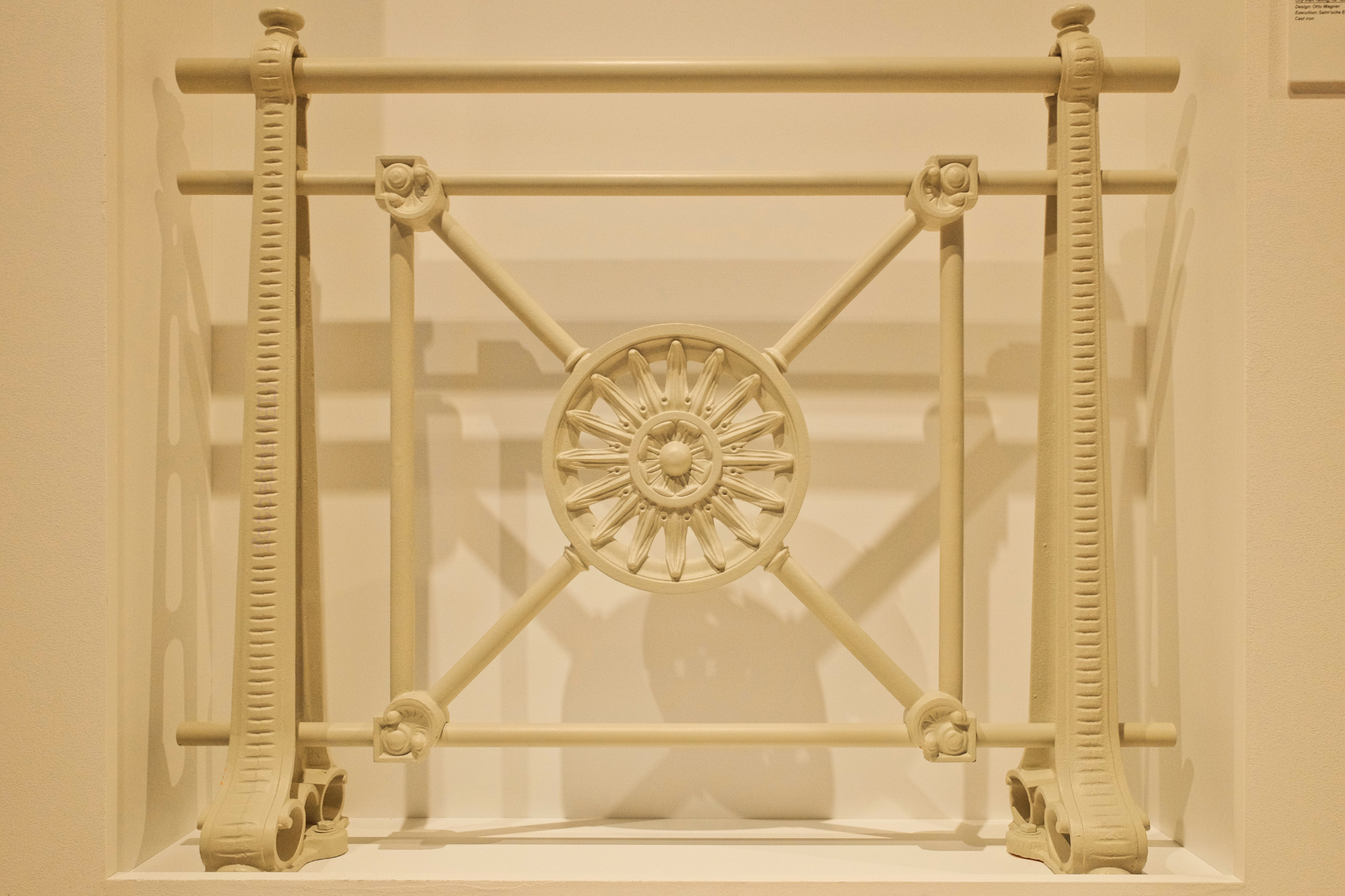

Cast-iron railing (c. 1894–1901) at Wagner’s city-rail Stadtbahn stations; Wagner-creation based on an old Roman design with a characteristic blossom at centre. Wien Museum Karlsplatz; photo, 10 Jul 2025 (X70).

Wien Museum Pavillon Karlsplatz, 1898

Display: Permanent exhibition of Wagner’s life and work inside former train station building Pavillon Karlsplatz.

Address: North side of Karlsplatz, in the 4th district (Wieden).

Public transport: U-Bahn U1, U2, or U4, to station “Karlsplatz.”

Designed by Wagner, two pavilions for Karlsplatz station were designed by Wagner; construction for the city railway was completed in 1898. One of the two buildings hosts the Wien Museum Otto Wagner Pavillon Karlsplatz. The second station building (not shown) houses a café and club. Photo on 16 May 2018 (X70).

1985 model of Steinhof Church, exhibition at Wien Museum Otto Wagner Pavillon Karlsplatz. Photo, 16 May 2018 (X70).

Baden bei Wien: Villa Hahn, 1885

Villa for the Hahn family.

Address: Weilburgstrasse 83–85, in Baden bei Wien (southwest from Vienna).

Public transport, from Baden bei Wien Bahnhof: VOR bus 308 to stop “Strandbad”.

Villa Hahn. Photo, 9 Jun 2023 (X70).

Villa Hahn. Photo, 9 Jun 2023 (X70).

Baden bei Wien: Villa Epstein (Rainer), 1867

Villa initially built for and commissioned by Epstein family (i.e., Palais Epstein in Vienna); villa sold to Archduke Rainer in 1873

Address: Rainerweg 1, in Baden bei Wien (southwest from Vienna).

Public transport, from Baden bei Wien Bahnhof: VOR bus 308 to stop “Strandbad”; VOR bus 358 (CityBus B) to stop “Kornhäuselstrasse”.

Villa Rainer, from the access road. Photo, 9 Jun 2023.

“Italian-style country house.” Photo, 9 Jun 2023.

Information signage about Villa Rainer from Wienerwald & Land Niederösterreich. Photo, 9 Jun 2023.

Sources

• Architektenlexikon Wien 1770–1945; available at <https://www.architektenlexikon.at/de/670.htm> [accessed Nov 2023].

• Bernabei, G., Otto Wagner (Zürich: Verlag für Architektur Artemis, 1986). Available from archive.org: <https://archive.org/details/ottowagner0000bern> [accessed Nov 2025].

• Geretsegger, H. & Peintner, M.; Otto Wagner 1841–1918: The Expanding City, The Beginning of Modern Architecture, English translation (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1970).

• Kortz, P., Wien am Anfang des XX. Jahrhunderts, 1–2. Bände (Wien: Gerlach & Wiedling, 1905). Available from archive.org: volumes one and two [accessed Nov 2023].

• Öser, C., Otto Wagner in Wien: Erbe eines Visionärs, 10 April 2018, <https://coeser.de/blog/index.php/2018/04/10/otto-wagners-wien-erbe-eines-visionaers/> [accessed Nov 2023].

• Öser, C., Otto Wagner in Wien: Die unbekannten Schätze, 17 April 2018, <https://coeser.de/blog/index.php/2018/04/17/otto-wagners-wien-die-unbekannten-schaetze> [accessed Nov 2023].

• Parsons, N., Vienna: A Cultural History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

• Sarnitz, A. (ed.), Architecture in Vienna (Wien: Springer-Verlag, 1998).

• Sarnitz, A., Otto Wagner 1841–1918: Forerunner of Modern Architecture (Köln: Taschen, 2005).

• Schorske, C.E., Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (New York: Alfred E. Knopf, Inc., 1980).

• Smith, D.J.D., Only In Vienna: Guide to Unique Locations, Hidden Corners, and Unusual Objects, 4th edition, (Only In Guides/The Urban Explorer; New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015).

• Vergo, P., Art in Vienna, 1898–1918: Klimt, Kokoschka, Schiele, and their Contemporaries (Ithaca: Cornell University, 1981).

• Wagner, O., Einige Skizzen, Projecte, und ausgeführte Bauwerke, 1–4. Bände (Wien: Kunstverlag Ant. Schroll v. Comp., 1890–1922). Available from Wien Bibliothek: <https://www.digital.wienbibliothek.at/wbrobv/content/titleinfo/1948214?query=Einige%20Skizzen%20Projekte%20Ausgef%C3%BChrte%20Bauwerke> [accessed Nov 2023].

( Back to the list )

I made all photos above in the summers of 2018, 2022, 2023, and 2025 with these devices: Canon EOS6D mark1 (6D1), Fujifilm X70 fixed-lens prime (X70), and iPhone15 (P15). Alle Fotoaufnahmen sind von Wasserzeichen versehen worden. This post appears on Fotoeins Fotografie at fotoeins DOT com as https://wp.me/p1BIdT-bIA. Last edit: 23 Jan 2026.

25 Responses to “Vienna: Otto Wagner’s architectural legacy”

[…] to the grand St. Leopold church at Steinhof, which he completed in 1907. Not surprisingly, the Steinhof church resembles the earlier Nepomuk chapel, especially the rounded […]

LikeLike

[…] Also, the Epstein family commissioned architect Otto Wagner to build a summer palace in nearby Baden bei Wien in […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] European counterparts. As early as 1895, essentially the most distinguished architect of the day, Otto Wagner, introduced the top of historicist and romanticist structure, which had dominated the earlier many […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] çok daha erken başladı. 1895 gibi erken bir tarihte, dönemin en önde gelen mimarı, Otto Wagnerönceki on yıllara hakim olan tarihselci ve romantik mimarinin sonunun geldiğini duyurdu; artık […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] earlier than its European counterparts. As early as 1895, the most prominent architect of the day, Otto Wagner, announced the end of historicist and romanticist architecture, which had dominated the previous […]

LikeLike

[…] his architectural fingerprints all over Vienna. It’s worth some time to look for some or all of these, if you’re wondering about his massive impact on the city’s evolution in the early […]

LikeLike

[…] Wagner’s architectural and design legacy from the early 20th-century is predominantly secular, remaining visible throughout the city […]

LikeLike

[…] included this building as part of my description of Otto Wagner’s architectural legacy in Vienna and of the recent centenary celebration in Vienna of the city’s 19th- to 20th-century […]

LikeLike