Above/featured: Karlsruhe Palace.

You won’t likely find another German city in the shape of a fan.

Sitting pretty near the Rhine river in southwest Germany, Karlsruhe is known as the “Fächerstadt” (“fan city”) for its very specific shape.

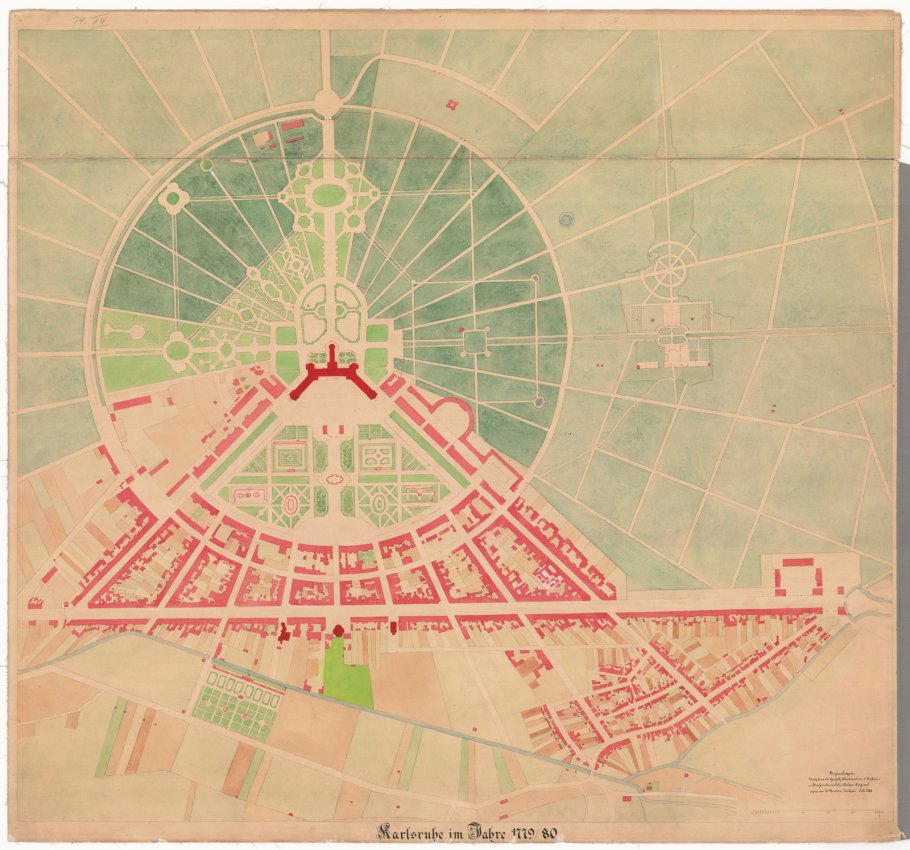

On 17 June 1715, Margrave1 Karl Wilhelm (Charles William) of Baden-Durlach celebrated breaking ground and the first laid stone for his new residence, palace, and seat of power. The story goes that after a vivid dream, Karl Wilhelm decided to build his new home of “rest and relaxation” (“Karls Ruhe”) in the middle of a nearby forest. A planned city would surround the palace, an appropriate symbol for the question of “who ruled whom.” The palace sat at the central hub of 32 “rays” or streets radiating outwards: 9 streets to make up the new city, and 23 for the palace gardens. Emerging from the palace was the “Via Triumphalis,” the north-south central axis road into the city. Karl Wilhelm moved the margraviate seat from nearby Durlach to the “new shiny city” of Karlsruhe upon completion of the new palace in 1718.

In the spring of 1788, Thomas Jefferson, while serving as America’s chief of mission (Minister Plenipotentiary) in France, embarked on a tour of Holland and the Rhine river in what is now Germany. He stayed in “Carlsruh”2 on 15 and 16 April 1788. Impressed by what he saw throughout his trip, he sent a letter and sketches3 to Pierre Charles L’Enfant4 who was charged by George Washington with the design and construction of a new American capital city. Jefferson wrote to L’Enfant on 10 April 1791:

“…in compliance with your request I have examined my papers and found the plans of Frankfort on the Mayne, Carlsruhe, Amsterdam Strasburg, Paris, Orleans, Bordeaux, Lyons, Montpelier, Marseilles, Turin and Milan, which I send in a roll by this post. They are on large and accurate scales, having been procured by me while in those respective cities myself. …”

With copies of European city plans in hand, these plans provided inspiration for L’Enfant’s eventual design for Washington, DC.

The Badisches Landesmuseum has occupied the palace since 1921, and the city of Karlsruhe celebrated its 300th anniversary5 in 2015.

What would Thomas Jefferson have seen?

Dated between 1739 and 1779, the following four maps from Stadt Karlsruhe city archives would have been representative of the young city at the time of Thomas Jefferson’s 1788 visit.

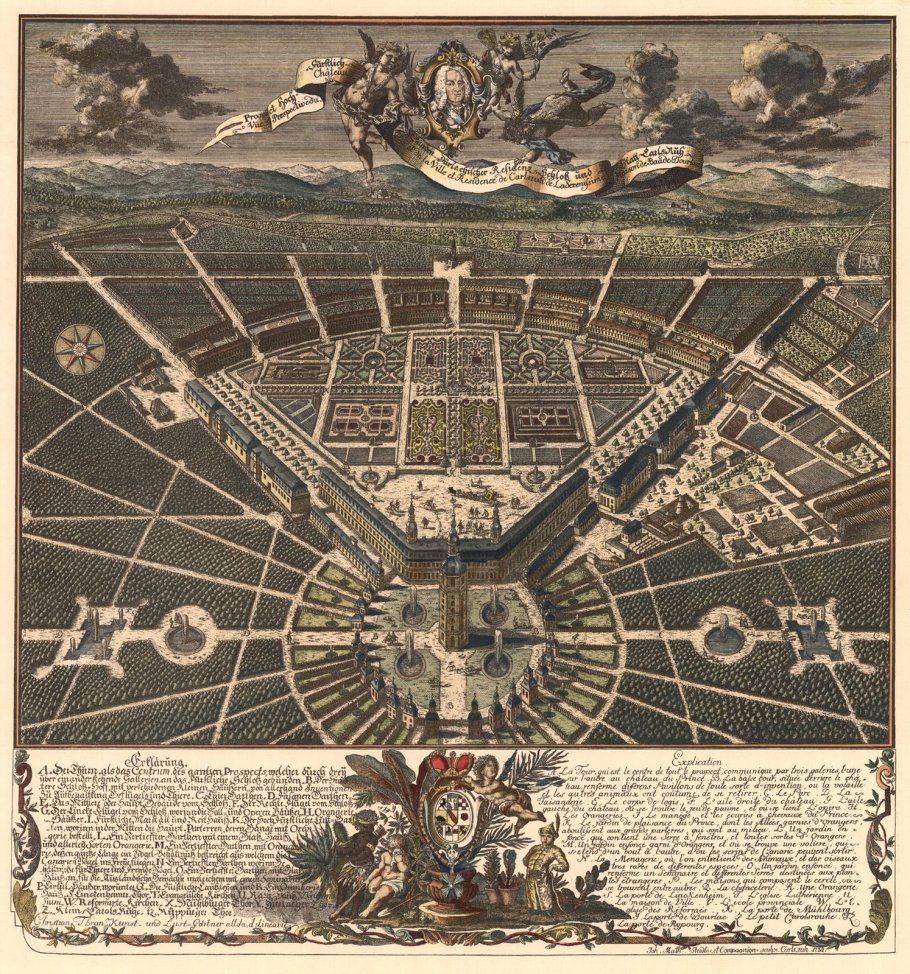

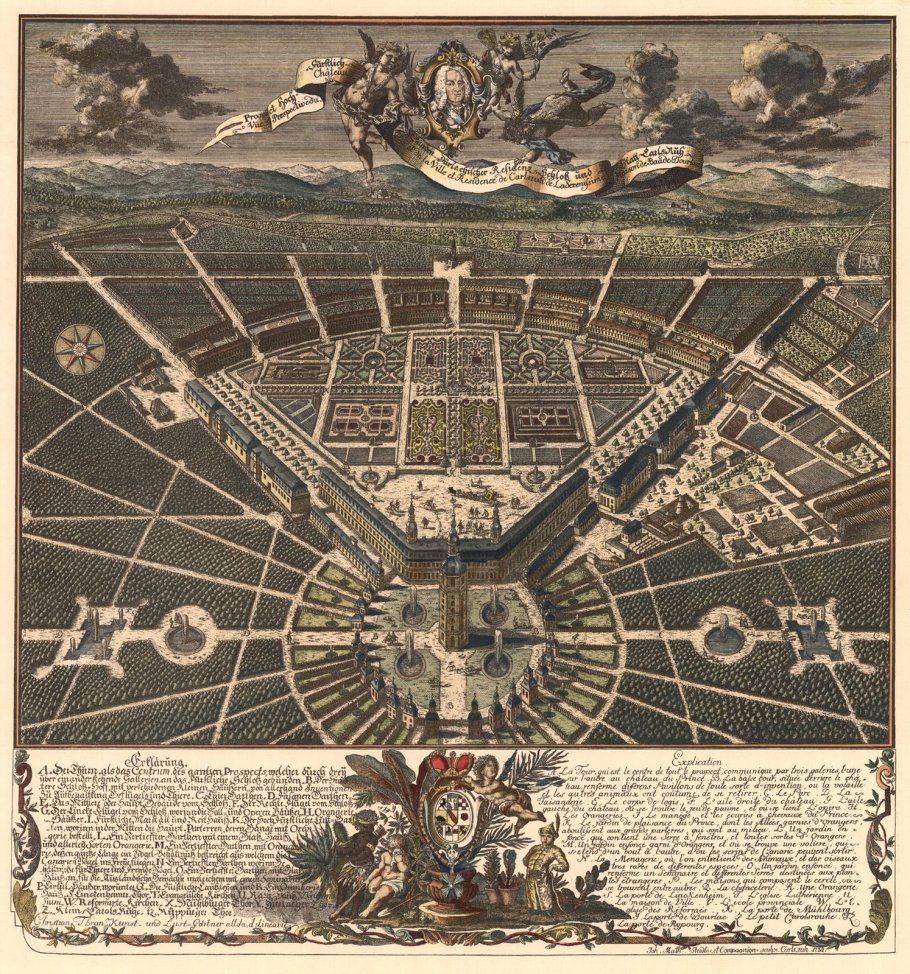

1739 city view with south at top; coloured copper engraving by Christian Thran.

1739 city view with north at top; the “fan” consists of 9 streets; coloured copper engraving by Christian Thran.

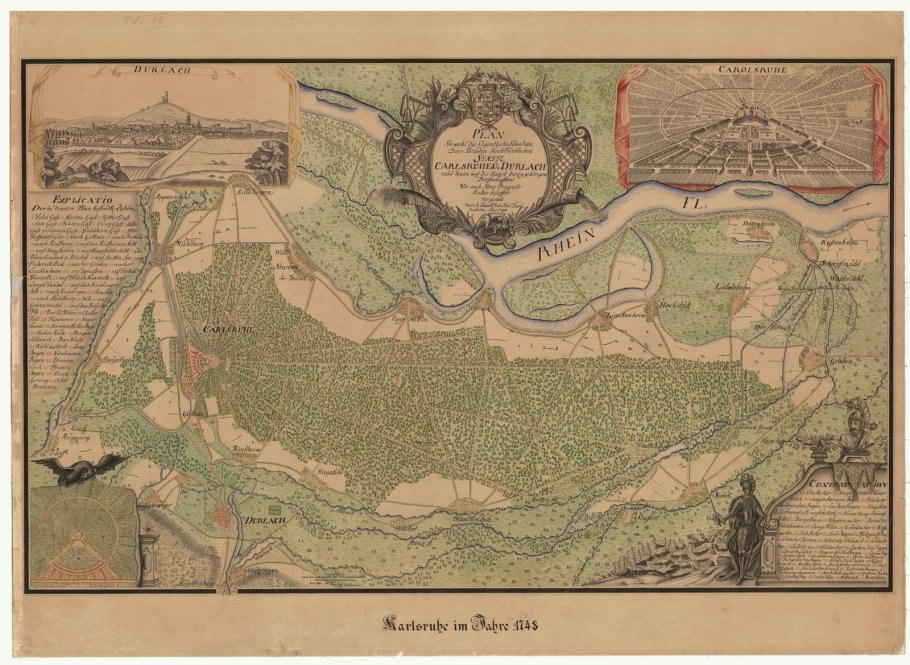

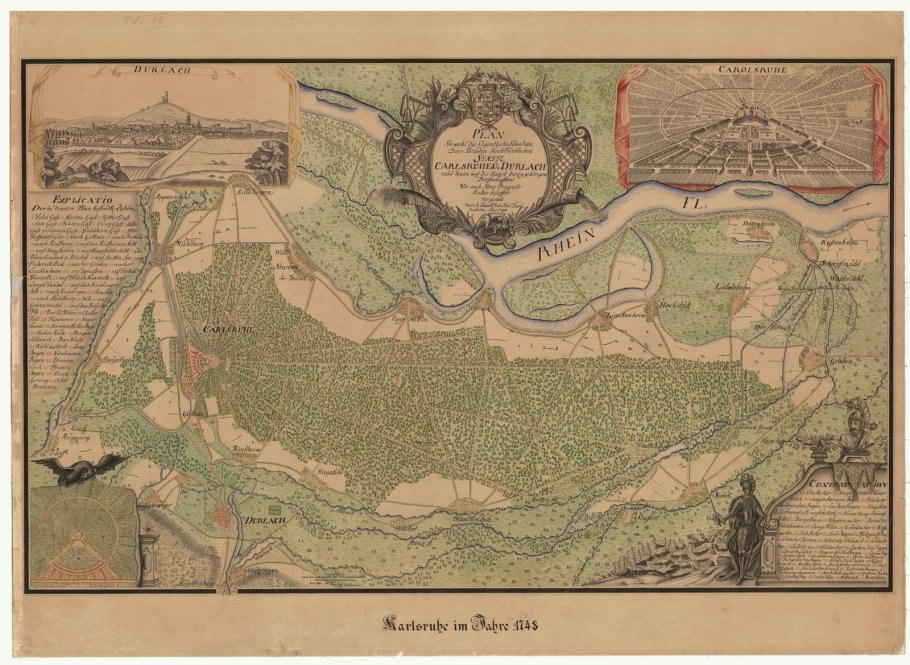

Map dated 1745 of “Carlsruhe” (Karlsruhe), Durlach, and surroundings, with west at top, towards the Rhine river (Rhein Fl.).

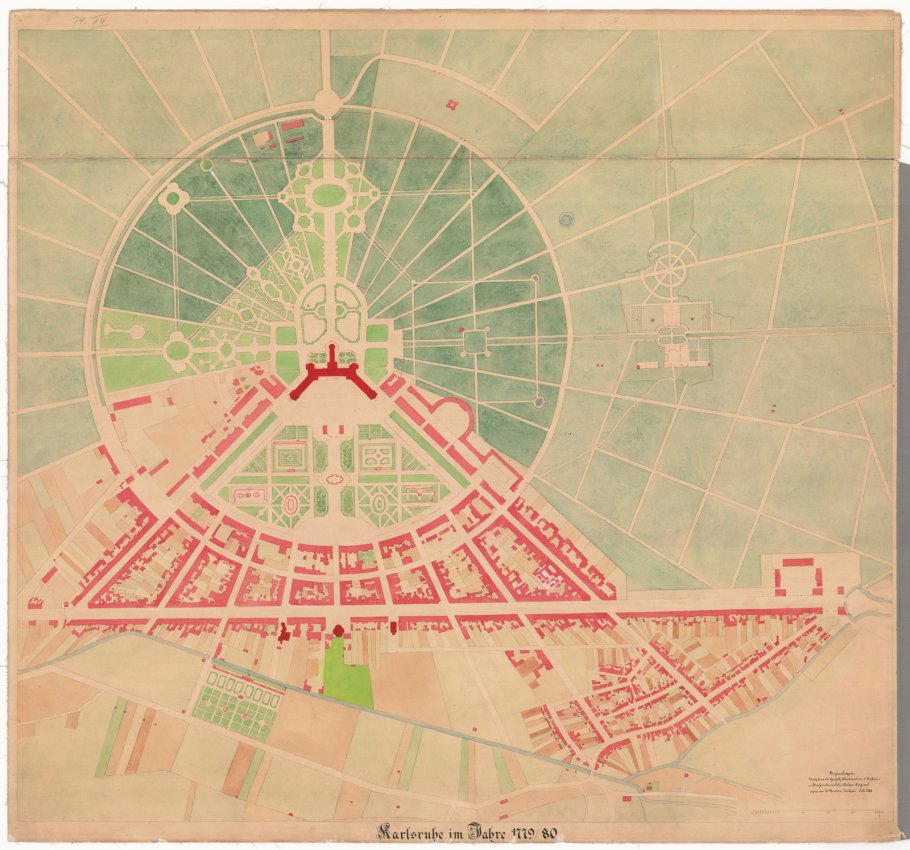

1779 city map: north at top, Schloss (palace) at circle’s centre. Note how palace “wings” extend south into a “fan” of 9 streets into the young city.

Panorama from the Palace Tower

Even in the dreary days of late-fall and early-winter, there are sweeping views of the city and surrounding area from the top of the Schlossturm (Palace Tower); even the tower’s stairs are themselves a highlight of geometry. It’s also important to realize 14 kilometres to the German-French border isn’t far at all.

Up the palace tower (HL).

South view, along Via Triumphalis through Schlossplatz (palace square). The hills in the background are about 10 kilometres distant (HL).

Wide south view with the Via Triumphalis north-south axis at centre. Note palace “wings” at far-left and -right, making the “fan” into the city (HL).

Southwest, to Bundesverfassungsgericht (Federal Constitutional Court) at centre-right, just beyond the palace (HL).

Northwest, towards Majolika Manufaktur Karlsruhe at upper right (HL).

North-northeast to Schlossgartensee (palace garden lake) at centre-left and Wildparkstadion (stadium) at right (HL).

Northeast: Wildstadion at left, Grossherzogliche Grabkapelle at centre in the distance (HL).

Facing east; Grossherzogliche Grabkapelle at far left in the distance, Kirche St. Bernhard at right to the southeast (HL).

Facing southeast; Kirche St. Bernhard at left, and beyond Schlossplatz at centre is Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) Campus Süd (HL)

Return to the south-facing view of Schlossplatz, or palace square (HL).

Down the palace tower (HL).

Notes

1 A “margrave” was a hereditary title for a prince in the Holy Roman Empire; their territory was called a “margraviate” (Markgrafschaft). Margraviate Baden-Durlach and neighbouring Margraviate Baden-Baden reunited in 1771 to form the Margraviate of Baden. After dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the Grand Duchy of Baden was created as a member state within Napoleon’s Confederation of the Rhine.

2 “Notes of a Tour through Holland and the Rhine Valley, 3 March–23 April 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-13-02-0003. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 13, March–7 October 1788, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956, pp. 8–36.]

3 “XII. Thomas Jefferson to Pierre Charles L’Enfant, 10 April 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-20-02-0001-0015. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 20, 1 April–4 August 1791, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982, pp. 86–87.]

4 More about Pierre Charles L’Enfant appears at the US Library of Congress.

5 Wulf Rüskamp wrote this article for the Badische Zeitung (in German).

Thanks to Karlsruhe Tourismus and Hotel Rio Karlsruhe for a warm welcome and access to venues and services. Old city maps are from Stadt Karlsruhe’s archives. I made all remaining photographs on 17 November 2015 with a Canon EOS6D mark1. This post appears on Fotoeins Fotografie at fotoeins DOT com as http://wp.me/p1BIdT-8Cv.

49.013513

8.404435