Dachau: nie wieder, never again

Where: KZ-Dachau, 20 km northwest from Munich, Germany.

What: The blueprint by which murder became a methodical industrialized process.

I once thought I wasn’t prepared emotionally; perhaps I never would. But I couldn’t go further in my long-term examination of Germany and Jewish-German history without a visit.

It’s an overcast morning in early June, and a couple of rain showers accompany me along with a handful of other people, waiting for the site to open at 9am. A dark heavy cloak descends the moment I step through the main gate and into the site. There is dread, waiting. I promise myself to be open as much as possible, to really look and listen.

This is KZ-Gedenkstätte Dachau, the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site. The abbreviation KZ is “Konzentrationslager für Zivilpersonen” or concentration camp for civilians, although the initial terminology used by the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS) was KL for “Konzentrationslager.”

There’s a lot to absorb. And maybe, it’s best not to.

Systematic torture and unrestrained cruelty. Forced medical experiments. Arbitrary execution by hanging or gunfire. The destruction of human dignity. The annihilation of hope. This camp as a “model” to broaden the scope and scale of industrial mass-murder. The first commandant of Auschwitz in 1940, Rudolf Höss, honed a career in brutality as SS support staff and block leader at the Dachau camp in late-1934.

I had planned to stay for a few hours at most and leave around noon. I didn’t notice the time. When I finally noticed clear skies and the change in sun-angle, I check my watch. It’s almost 5pm, closing time. Eight hours have flown by outside my bubble, which begins to dissolve.

In March 1933, the Nazis established a concentration camp for political prisoners in the town of Dachau, 20 kilometres (12 miles) northwest from Munich. The Dachau concentration camp began as a holding place for political opponents and prisoners. In short time, the SS took over command, and the camp would take on different people from around Europe, functioning as the model for the operation of subsequent concentration and extermination camps. For 12 years until 1945, over 200-thousand people were imprisoned at the camp; over 43-thousand died here. Allied troops liberated Dachau concentration camp on 29 April 1945. Twenty years later in 1965, the former concentration camp reopened as a memorial- and education-site.

2020 marks the 75th anniversary of the liberation of concentration- and extermination-camps throughout central and eastern Europe.

“Wenn die Generation die den Krieg überlebt hat nicht mehr da ist, wird sich zeigen ob wir aus der Geschichte gelernt haben.”

(When the generation that survived the war is no longer with us, we’ll find out whether we’ve learned from history.)– Kanzlerin Angela Merkel, Bundespressekonferenz, 20 July 2018.

(German chancellor Angela Merkel, at Federal Government Press Conference).

“Unless the world learns the lessons these pictures teach, night will fall. But, by God’s grace, we who live will learn.”– “German Concentration Camps Factual Survey” documentary by Sidney Bernstein, co-written by Richard Crossman. [also, Stuart Jeffries, for The Guardian, 9 Jan 2015.]

Sections

There are many visuals below, and much of it is disturbing. Although I view everything presented as important, it’s not a complete overview of my visit. Instead, they’re parts and places and memories that have stayed.

- Main camp, one

- Crematoria area

- Jewish memorial

- Catholic Mortal Agony of Christ Chapel

- Protestant Reconciliation Church

- Main camp, two

- The bunker

- Book of Remembrance

- Last look

- Lee Miller’s correspondence

- Directions

Main camp, one

• Prisoner disembarkation, in front of the Jourhaus.

• Jourhaus, through which is misery, abuse, torture, and death.

• Roll-call square (Appellplatz).

Image from Dokumentationszentrum Obersalzberg in Berchtesgaden, along with my translation – 26 May 2018.

In front of the Jourhaus (SS offices): the grass-lined former railway track and adjacent crumbling cement platform lead the eye to the memorial site’s front metal gate with the cynical message about “work setting people free”.

Inside the front gate is the wide expanse of the roll-call square.

Security fence, near the crematoria area. Prisoners who approached the fence were shot by guards without warning; some ran deliberately into the fence to commit suicide.

Crematoria area

At the northwest corner is the area with two crematoria.

Entrance to the crematoria area; the caption reads “remember how we died here.”

Crematoria area: 1950 Fritz Koelle memorial sculpture of the unknown prisoner. The caption reads “In honour of the dead, a warning to the living.”

Exterior, crematorium number 1. About 11-thousand prisoners were cremated here between 1940 and 1943. Within a year of initial operation, camp authorities built a second and larger crematorium.

Exterior, crematorium number 2, known also as “Barrack X” (1943-1945).

Many executions by hanging took place next to the four ovens in crematorium number 2.

The gas chamber inside crematorium number 2 was used to kill by poison gas individuals and small groups of people. This “smaller” gas chamber became a direct predecessor to the large scale annihilation and mass-killing to come at extermination camps like Auschwitz.

A memorial to the murdered; this very location had once been an execution site.

Another execution site with a front shallow trench for blood.

Execution wall.

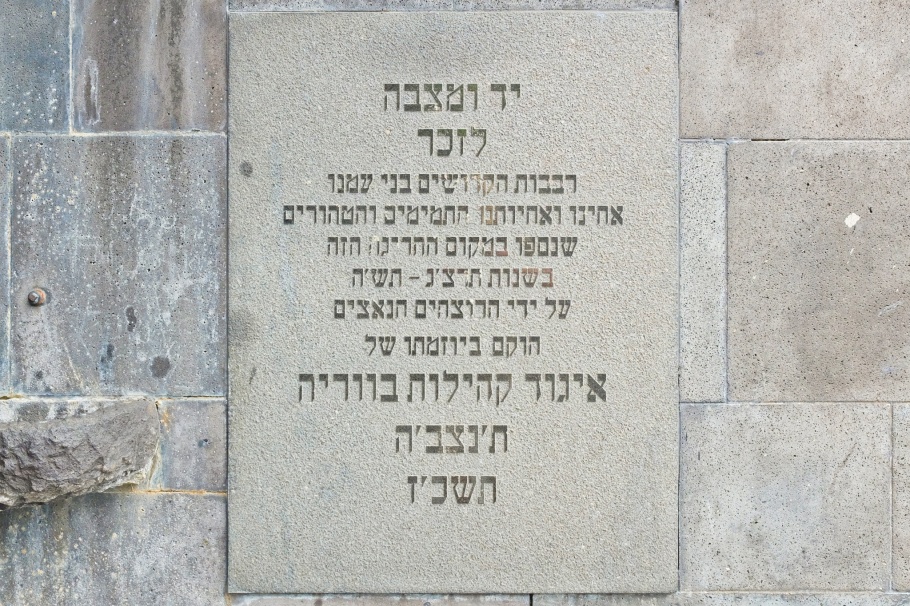

Jewish Memorial (1967)

The Jewish Memorial site was built according to plans designed by architect Hermann Ziwi Guttmann. The symbolic architecture is a direct reminder of the murder of European Jews. The ramped path leads down into the structure’s interior, where visitors see a vertical band of light-coloured marble pointing upwards to the opening in the roof and a menorah. With its origins from Israel, the marble symbolizes the continuity of Jewish life. The Jewish Memorial was officially inaugurated on 7 May 1967.

Entrance to Jewish memorial site.

Jewish memorial site.

Commemorative memorial to Jewish martyrs who perished during the Nazi reign of terror from 1933 to 1945: their deaths are both warning and obligation to remember. Established by the Israel Office of Cultural Affairs and communities in Bavaria, 1967 (year 5727).

At the very end is a column of light-coloured marble.

The marble column reaches up to a menorah at top.

Over 6 million Jewish people fell victim to Nazi tyranny.

Catholic Mortal Agony of Christ Chapel (1960)

The initiative for building the Catholic Mortal Agony of Christ Chapel came from survivor and former Dachau prisoner Johannes Neuhäusler (1888-1973) who would later become the bishop suffragan for Munich. The memorial was designed by architect Josef Wiedemann, and inaugurated on 5 August 1960 during the Eucharist World Congress. A path behind this chapel leads through a former guard tower and into the Carmelite convent built in 1963-1964.

Entrance.

Open interior and central altar.

From the inner altar, looking out and south along the camp road.

Mounted on the rear exterior wall is a memorial plaque in Polish, German, French, and English. “Here in Dachau every third victim was a Pole. One of every two Polish priests was martyred. Their holy memory is venerated by their fellow prisoners of the Polish clergy.”

Protestant Reconciliation Church (1967)

With the urging of survivors and the support from the World Council of Churches, the German Protestant Church built this Reconciliation Church. Architect Helmut Striffler designed both interior and exterior to avoid the severe symmetry and 90-degree architecture within the former concentration camp. This memorial was inaugurated on 30 April 1967. Staff members provide visitors church services, assistance and advice, and support for other events.“Die Versöhnungskirche wurde zum Gedächtnis der Opfer der Nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft von den Gemeinden der Deutschen Evangelischen Landes- und Freikirchen errichtet. Ihr Grundstein wurde am 8. Mai 1965 gelegt. Die Evangelischen Kirchen in Holland, Frankfreich, und Polen trugen mit Stiftungen zur Ausgestaltung bei.” (The Church of Reconciliation was built by the parishes of the German Protestant state- and free-churches in memory of the victims of Nazi tyranny. The foundation stone was laid on May 8, 1965. Evangelical churches in Holland, France, and Poland also contributed supporting donations to the effort.)

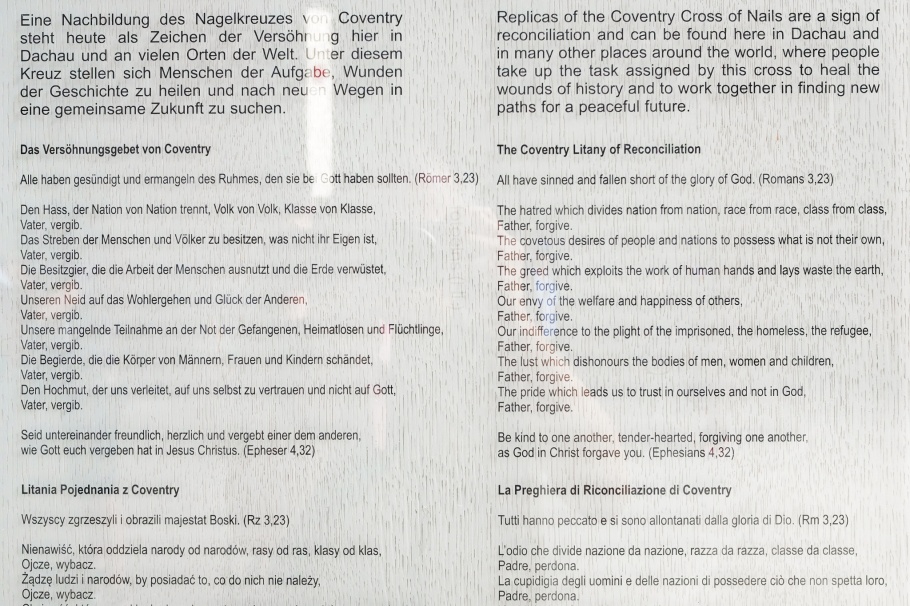

Every Friday at 1230pm, there is a short service at the Evangelische Versöhnungskirche (Protestant Reconciliation Church) to mark the Coventry association: Das Versöhnungsgebet von Coventry (Coventry Litany of Reconciliation). Present is a cross of nails from Coventry, England, dug out from the destroyed church caused by bombing in World War 2. Today, modest symbols like these in England and Germany emphasize ongoing efforts to reach forgiveness, understanding, and peace. (I found another cross of nails at the Herder City Church in Weimar, Germany.)

At 1230pm, I realize I’m the only one attending the service. The church deacon (Diakon) Klaus Schultz leads a one-to-one service in German. I follow some of the service, an understanding of context after many years of attending Protestant Sunday services; I follow the rest with the accompanying pamphlet printed in German.

My thanks to Mr. Schultz for carrying out the daily service to a congregation of 1, and his patience in putting up with my modest German.

West entrance, Protestant Reconciliation Church.

Modest Protestant chapel.

Commemorative Coventry prayer service every Friday at 1230pm, accompanied by cross of nails from Coventry church.

Das Versöhnungsgebet von Coventry / Coventry Litany of Reconciliation.

The 23rd Psalm.

East entrance, Protestant Reconciliation Church.

Main camp, two

During the reconstruction phase of the camp in 1937-1938, prisoners were forced to construct the very barracks in which they were to be housed. In total were 34 barracks buildings, each supposed to house up to 200 people; soon, each building would overflow with more than 2000 prisoners. All barracks were eventually demolished between 1962 and 1964.

Near the northeast corner of the memorial site, facing south: at left is a watchtower along the eastern wall, at centre in the background is a 1965 reconstruction of barracks A (distance about 1 km) and foundations of other barracks towards the right.

Foundations to former barrack number 30 in the foreground; camp road at left, facing south.

The prisoners’ infirmary were located in barracks A, B, 1, 3, 5 and 7, where prisoners were forced to undergo medical experiments by the SS, including malaria, phlegmon (inflammation of soft tissues), high-altitude, and hypothermia. For many, the infirmary would be their place to die.

Barracks number 1 was where malaria and phlegmon (inflammation of soft issues) experiments were carried out.

The international monument includes the 1968 bronze sculpture by Holocaust survivor Nandor Glid; the network of skeletons look like a barbed-wire fence, and represent prisoners who died from disease and starvation. An additional monument prints “Never again” in multiple languages and a 1967 memorial containing the ashes of an unknown prisoner.

International monument: 1968 bronze sculpture by Nandor Glid. Shapes of people seem to be stuck onto barbed wire.

International monument: “Never again”.

The bunker

The dreaded “bunker” was a prison within the camp where the SS could dole out additional terror. Punishment for individual prisoners included confinement in dark tiny cells for weeks to months, and torture and beatings by SS guards. Many were murdered inside the prison or executed outside. After 1943 until the camp’s liberation in 1945, most executions were carried out next to the crematoria.

The bunker, SS-controlled prison within the camp.

Approaching closing time for the site, I’m the only visitor inside the former bunker. The cries and screams of agony, fear, and terror seem etched deeply into the walls; perhaps, apparitions remain here, too.

In the bunker courtyard, SS guards applied pole-hanging and shot prisoners. Soviet prisoners of war, resistance fighters, and SS-members condemned to the death penalty were executed here.

Georg Tauber’s 1945 sketch of pole-hanging (Pfahlhängen) form of torture at Dachau camp. Minor infractions resulted in an hour on the pole, often resulting in severe wrist- and shoulder-injuries.

The green space behind the bunker seems superficial; torture and executions would have also taken place here.

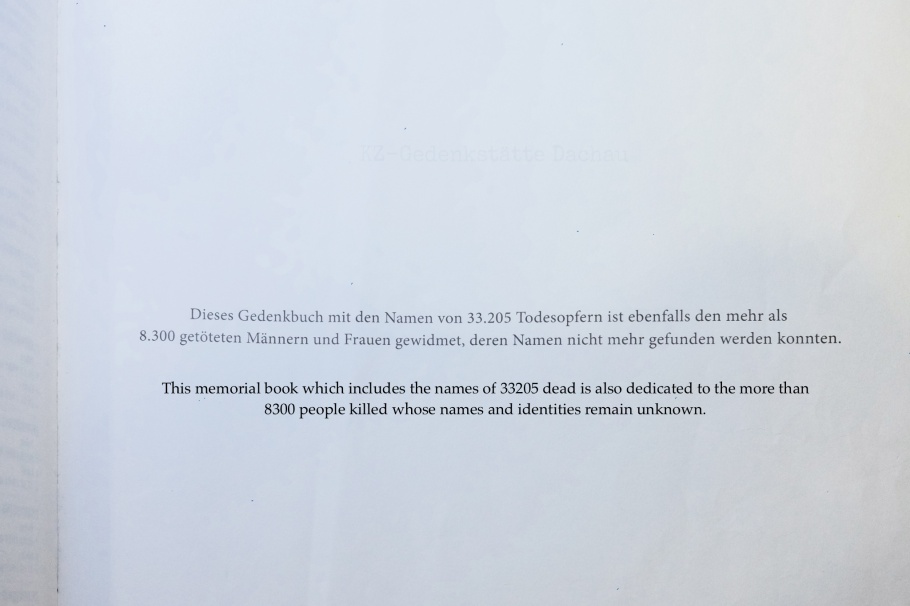

Book of Remembrance

Inside the former maintenance building, I’m inside a small memorial room off to the side of the museum’s exhibition area. A thick hardcover book is open; the title is “Book of Remembrance for the Victims of Dachau Concentration Camp“. Inside these pages are 33205 names; the actual count is much higher with thousands whose names have not been identified.

I turn the book over towards the middle, and I read individual names: … Landsberger, Landshut, Landsmann, Landtmann, Landzettel, Lanemann, Lanfranco …

If I say them out loud, I want to believe that these human beings existed and lived, that they’re recognized and they’ve come to life again, and that they will not be forgotten.

Book of Remembrance for the Victims of Dachau Concentration Camp.

I’ve included my translation in this image.

Names of the victims: LANDSBERGER to LANGER, from upper-left to lower-right, respectively.

Last look

In the final days of the war in April 1945, exhausted and malnourished prisoners from Dachau were forced to walk south in the “death marches”; many would die from abuse, execution, hunger, or cold. At Reichersbeuern/Waakirchen (near Bad Tölz in southern Bavaria), 17 year-old Lithuanian-Jew Isia Rosmarin pushed his valuable accordion into the hands of Friedrich Kunstwald, and asked him for something to eat. The 14-year old Kunstwald ran to his mother who gave him a piece of potato bread for Isia. Isia Rosmarin was liberated by US soldiers at Waakirchen on 2 May 1945.

Isia Rosmarin’s accordion.

Memorial to forced evacuation and death march of prisoners from Dachau, 1991 bronze sculpture by Hubertus von Pilgrim. “Hier führte in den letzten Kriegstagen im April 1945 der Leidensweg der Häftlinge aus dem Konzentrationslager Dachau vorbei ins Ungewisse.” / In the final days of the war in April 1945, prisoners from the Dachau concentration camp were forced to walk out into the unknown.

Hubertus von Pilgrim’s 1991 bronze memorial sculpture to forced evacuation and death march of prisoners from Dachau.

After the 5pm closing time, stillness reigns over the site. Roll-call area (foreground), international Holocaust monument (mid-ground), former maintenance building with permanent exhibitions (background).

Documentary about Dachau concentration camp, from Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR Fernsehen, TV-Doku “KL Dachau”).

Lee Miller’s Correspondence

Lee Miller had already established herself as model, photographer, and artistic contributor to the Surrealist movement in the early 20th-century. But her curiosity could not be quenched; her need to learn and discover were strong motivations.

During World War 2, Lee Miller was the only woman combat photographer to follow the advance of Allied forces across western Europe. Serving as war photographer and reporter for U.S. Armed Forces and writing copy to accompany her photographs, she became a photojournalist who would also ask questions about the war’s aftermath on survivors, especially on women.

Miller entered the Dachau camp on 30 April 1945, one day after soldiers from U.S. (Allied) forces had liberated the camp. In her journal, she wrote:

… I arrived in Dachau on the night of 30 April as blackout and shells were falling. The camp has been liberated by the combined operations of the (U.S.) 42nd and the 45th Infantry Divisions. Just outside of a picturesque town, it was typical of all great Nazi concentration camps, a large barrack area of oblong buildings. Half of the camp was a permanent billet for SS troops, the remainder for starved, half crazed prisoners.In this case the camp is so close to the town that there is no question about the inhabitants knowing what went on. The railway siding into the camp runs past quite a few swell villas and the last train of dead and semi dead deportees was long enough to extend past them. The cars are still full of skeletal dead, and the path beside the trains are littered with the fleshless bodies of those who tried to get out and walk to their execution.

The SS barracks are empty although the roads between are decorated with the battered carcasses of soldiers. The dog kennels are vacant – one dead dog lies on the grass. The small canal bounding the camp was a floating mess of SS, in their spotted camouflage suits and nail-studded boots. They slithered along in the current, along with a dead dog or two and smashed rifles. Prisoners and soldiers tried to fish out some of the bodies.

One block is an Angora rabbit farm where the rabbits are an industry of the prison. They are much less crowded and better cared for than humans, beautifully clean and housed – lovingly looked after by Capo prisoners. The stable of work-horses was also perfection, with fat-bottomed beasts which shocked the eye after so many emaciated humans.

The crematorium was out of fuel for long enough to pile up two rooms of bodies. The gas chambers look like their titles, written over the doors, ‘SHOWER BATHS’. The elected victims having shed their clothes walked in innocently, leaving their prison clothes behind them, to be bathed and deloused. Turning on the taps for the bath, they killed themselves, thereby saving the SS the stigma of being murderers.

The overcrowded blocks of prisoners were recrowded by incoming evacuated prisoners from other camps. The triple decker bunks, without blankets, or even straw, held two and three men per bunk who lay in bed, too weak to circulate the camp in victory and liberation marches or songs, although they mostly grinned and cheered, peering over the edge. In the few minutes it took me to take my pictures, two men were found dead, and were unceremoniously dragged out and thrown on the heap outside the block. Nobody seemed to mind except me. The doctor said it was too late for more than half the others in the building anyway. The bodies are just chucked out so that the wagon that makes the rounds every day can pick them up at the street corner, like garbage disposal.

All over the camp are heaps of clothing – dirty soiled rag piles – civilian clothes from the immediately executed and prisoner clothes from the dead. Prisoners were prowling these heaps, some of which were burning, in the hopes of finding something more presentable than what they were wearing already. Naturally, the moment the guards of the camp were disposed of by very fine methods devised by the prisoners themselves they looted the warehouses of both the Nazi and the prisoner supplies. Only the strongest and most active of the prisoners could participate in this pleasure. Anyone able to wander around the grounds is pretty well off. There are thousands in the bunks who are too weak to scrounge or ever dress themselves again.

This camp was not designed for women, but in the last mintue evacuation of other camps as the Krauts retreated, about five hundred women were shifted here and were put into one block. They are mostly healthy ones who were worth bringing in for labor, although now there are many hospital cases including typhus. There are new-born babies and wildly insane people among them. They are cared for by a Viennese woman doctor Dr Ella Lingens, LLD MD also of the London School of Economics, as she is not only a doctor of medicine but also of law. She was imprisoned two and a half years ago for having helped hide Jewish women. She has a six-year-old son, she hopes, in some Austrian village and a husband she has been unable to hear from all this time. The ward is the former camp brothel, hence it is better decorated than others with only two-decker bunks. Patients have already started embroidering signatures of other prisoners and of their head nurse on terrible towels etc. Other girls are sewing scraps of colored cloth into their national flag boutonnières.

Trucks arrived and began unloading food, looted officially from German warehouses. Prisoners climbed on roofs, celebrating, singing hymns and national anthems in honor of the birthday of a Dutch princess, cheering everything they can think of and finally sorting out three strips of colored material, not yet sewn together, but which will make their national flag.

Dachau is the prison for the cream of the crop – nearly all political prisoners. It is here that Niemoeller, Schuschnigg and others were until last week. We hoped to find some of them, but the Krauts took many with them, probably to their last stand in Munich as hostages. There remained many journalists, such as Philippe Brundt of ‘Le Peuple’ and ‘Le Soir’, Bruxelles and Leurs Vancoeverde, a Dutchman who had been correspondent for ‘United Press’. Also ex-ministers and intellectuals such as Wladimir Paulin, Czech Minister of Finance and Professor in Prague University, Dr. Jindra Polak, who was chief of the General Hospital, Prague, and Jospeh Hrnicko, general manager of a famous glass works.

Soldiers were encouraged to ‘sightsee’ around the place, they were abetted to photograph it and tell the folks back home. However, by midday, only the press and medics were allowed in the buildings, as so many really tough guys had become sick it was interfering with duties.

Tomorrow – Munich.

Excerpt from “Lee Miller’s War: Photographer and Correspondent with the Allies in Europe 1944-45“, ed. Antony Penrose, Bullfinch Press, pp. 181-187 (1992). Her images of the camp, the dead, and the survivors are in the Lee Miller Archives; type “Dachau” in the search window.

Reproduction of photo made by Lee Miller on 30 Apr 1945, one day after the camp’s liberation.

Directions

From München Hauptbahnhof (Munich central station), take the S-Bahn S2 train northbound towards destination “Petershausen”. Disembark the train at “Dachau Bahnhof” (Dachau station), and not “Dachau Stadt” which is one stop too far. At Dachau Bahnhof, follow the signs to local buses. This is where bus 726 begins its route towards destination “Saubachsiedlung”. Hop onto bus 726 for the 7-minute ride, and with all stops announced and displayed, disembark the bus at stop “KZ-Gedenkstätte”. Follow the signs to the entrance of the memorial site. If you prefer to walk from Dachau Bahnhof, it’s 3 kilometres on foot from train station to memorial site.

I made all photos above with a Fujifilm X70 fixed-lens prime at Dokumentationszentrum Obersalzberg in Berchtesgaden on 26 May 2018 and at the KZ-Dachau memorial site on 1 June 2018. This post appears on Fotoeins Fotografie at fotoeins DOT com as https://wp.me/p1BIdT-aFB.

More

• Germany’s Darkest Places (2009): Der Spiegel, in English.

• International Holocaust Remembrance Day, held every 27 January to mark the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

• BR TV-Doku “KL Dachau”: Teil 1., “Das System“; Teil 2., “Im Lager“.

5 Responses to “Dachau: nie wieder, never again”

As a young child , I remember our class of Elementary school, back like 57 years ago, since I lived only a few kilometers away from Dachau,we did a field trip to Dachau Konzentration Camps. I still can remember my fearful thoughts as a child , those feelings have never left me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, Cornelia. I’m glad I gathered enough mental and emotional fortitude to have visited; I’m not going to forget the experience. And in these times, in all times, prejudice and racism must be called out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, Henry. Thank you for this. It’s a very moving testament to a horrible era in human history and the suffering of millions. i fear that we still haven’t learned the lessons from this time. Lee Miller’s account is very moving. I hadn’t read it before. The transcripts of the German concentration camp commanders from the Nuremberg Trials are equally moving in their callousness and indifference.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, Patti. Thanks for reading and for your comment. Yes, as humans, we have a great knack for repeating the worst. In the present circumstances, travel plans have gone up in smoke, and I was supposed to return to Nuremberg in a few weeks’ time to learn more about the Trials. That’s a good reminder to look online for information and testimony from the Trials. The one and only time I visited Nuremberg was way back in 2002: I remember the big Documentation Centre at the former rally grounds, but I also want to go back and combine that with a visit to the Courts where the Trials were held. I think Lee Miller’s life story is remarkable, and it’s worth noting how much she wanted to document life and events through images. But witnessing war and the consequences of Nazi depravity changed her, as her son Antony Penrose had once wrote. Thanks again, Patti.

LikeLike

[…] no. 2, built in 1942-1943: Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site. Photo: 1 Jun […]

LikeLike